1481798 Curiosities served

Viewpoint

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Read/Post Comments (6)

As I'm wrapping up my final draft of ANGELS FALLING, the third Derek Stillwater novel, I keep thinking of Robert Gregory Browne's comments that he writes from deep point of view. That means that although he may use multiple points of view, all observations are from the point of view character.Essentially I do this as well, although the distance I have from the narrative varies more than I want it to. That is to say, I try to keep the observations in the narrative to seem as if they are coming from the POV character, but sometimes I wander out into a more omniscient pov. (Hell, sometimes I've noted that I've wandered into other character's pov's unintentionally, and I have to change that--shame on me).

Like Mark I tend to find myself, quite unknowingly, becoming omniscient. But then point of view presents a constant conundrum.

Let's say, for example, that a novel begins, from my point of view, as I walk back up the hill to the house after hauling the trash down to the road. What novel would start this way, I can't say. It probably wouldn't be a thriller.

If I were to transcribe my active thoughts, I might mention noticing on the path a fallen limb which I have to step over, but I wouldn't describe the path. I'm used to the path. I don't give any thought to it. The same is true of the house as I approach. Yet, in order to visualize the scene, the reader would have to see the path and the house -- things I know so well that I don't think about them when I take out the garbage, particulalry in the morning when I'm still half asleep.

In order to set the scene I would likely describe details I'm not consciously thinking about, and to that extent I would be veering towards omniscience. True, the light falling on my retinas contains every detail of the world around me, but insofar as I don't consciously note this or that leaf out all the thousands which I can see on the trees along the path and under my feet or the color of the siding on the house, these things are not strictly speaking part of my viewpoint at that moment. At least if you define viewpoint as what a character is thinking.

No doubt, a writer might stick purely to a character's point of view, but usually there are compromises. Very often, or so it seems to me, the reader needs (and wants) to be shown more than what a character is actively thinking about at a given moment.

Depending on the desired effect, novels tend to move between various levels of viewpoint, sometimes plunging to the depths of stream of consciouness, other times threatening to break the surface into omniscience, often staying in the middle, combining what a character is actually thinking with what he or she knows and doesn't have to think about.

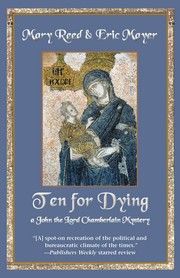

Mary and I tend to stay fairly near the surface when it comes to pov, which is probably rather old fashioned but what we like.

I was thinking about viewpoint a couple days ago while working on the first draft of the new Byzantine mystery. Our detective is walking the streets of Constantinople, conducting an investigation:

The workshop of the glassmaker Michri sprawled near the crest of the ridge overlooking the Golden Horn, at the edge of the Copper Market not far from the Great Church. John had been here before to commission glassware for imperial banquets and ceremonies.In the next chapter, John visits another craftsman who is briefly described:Any other Lord Chamberlain would have delegated that part of his official duties, but John enjoyed inspecting glass goblets destined for imperial tables. These were things of substance. John missed the weight of a sword in his hand. The secrets of the court, discreet advice, subtle political maneuverings, everything with which he dealt now, were insubstantial and the results of his efforts, more often than not, uncertain. It might be more satisfying to shape molten glass into a pleasing shape or turn up the soil of a field. In another life, he had envisioned himself retiring to a farm.

The mosaic maker was a paunchy, middle-aged man, utterly unremarkable in appearance, except for his hands whose exceptionally long fingers were as calloused as a bricklayer’s.

Although I don't make a point of saying "John noticed" it struck me that since he has been thinking about the satisfaction of working with one's hands, when he first saw the mosaic maker he might very well note the man's hands.

A small touch like that is probably not noticeable but I suspect such things, done consistently, might put the reader in the minds of the characters without even calling attention to it.

Read/Post Comments (6)

Previous Entry :: Next Entry

Back to Top